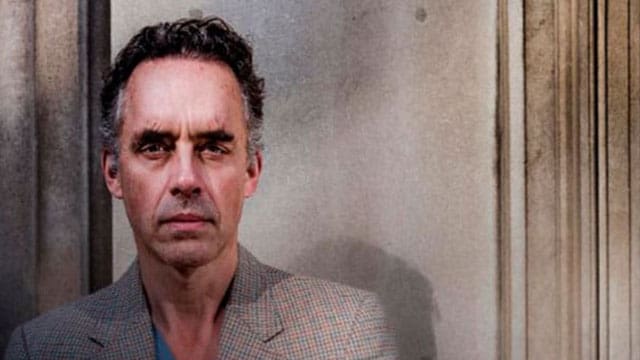

Jordan Peterson appeal rejection raises concerns about judicial and regulatory overreach in Canada’s justice system

By Colin Alexander

Universal problems in Canada’s judicial system have come to light with the rejection of Jordan Peterson’s appeal against Ontario’s College of Psychologists (CPO) in Divisional Court. The CPO had mandated that Peterson undergo re-education as a condition to retain his licence – as punishment for ridiculing public figures. But as Dr. Peterson stated in the National Post on October 11, they have failed to find someone to “brainwash” him.

The case sets a troubling precedent that unaccountable tribunals can override apparent Charter rights, declaring any dissenting opinion or peaceful protest unacceptable. This echoes the heavy-handed treatment of supporters of the 2022 Freedom Convoy protest on Parliament Hill. The implications extend beyond Peterson; all regulated professionals – doctors, lawyers, teachers – are now particularly vulnerable. Rather than acting as a check on overreach, the courts have become instruments of enforcement.

The roots of this issue were noted in 2018 by Chief Justice Richard Wagner, who called his court “the most progressive in the world” at a press conference covered by the Toronto Star. Today, “progressive” has become synonymous with the absurdities Peterson criticized. Wanjiru Njoya, a legal scholar at the University of Exeter, pointed out that courts routinely dismiss any perspectives outside progressive boundaries as unreasonable.

Compounding the issue is judicial bias. Canadian judges are increasingly presiding over cases where their impartiality is compromised by personal or professional connections. In the American Judicial Code, a clear standard is set: “Any justice, judge, or magistrate judge … shall disqualify himself in any proceeding in which his impartiality might reasonably be questioned.” Canada should take note.

Justice Paul Schabas, who wrote the decision on Peterson’s appeal, had a significant conflict of interest. In 2018, while leading the Law Society of Ontario (LSO), Schabas supported the controversial Statement of Principles (SOP) mandating that lawyers commit to Equity, Social, and (Corporate) Governance (ESG) as a licensing condition. The LSO ultimately withdrew the SOP following protests, such as African-Canadian lawyer Elias Munshya’s critique in Canadian Lawyer: “Lawyers play an essential role in our society; that role, however, does not include becoming state agents that parrot state-sponsored speech.”

Chief Justice Wagner’s recent comments highlight a foundational shift: courts now readily abandon historic common law precedents. Wagner remarked, “Apart from considering [historic] decisions as part of our legal cultural heritage, no one today will refer to a decision from 1892 to support his claim,” and added, “sometimes a decision from five years ago is an old decision ….” This perspective allowed the Supreme Court to disregard established precedents when it disqualified Marc Nadon from joining their club, as detailed in my book Justice on Trial.

The subjective interpretation of “reasonable” underpins much of Canada’s problematic jurisprudence, lacking objective criteria and enabling judges to favour allies while penalizing others. Justice Schabas highlighted Peterson’s comments as unacceptable, such as a May 2022 tweet criticizing a Sports Illustrated cover: “Sorry. Not Beautiful. And no amount of authoritarian tolerance is going to change that.”

Peterson argued that off-duty opinions should not be constrained by the CPO’s Code of Ethics, which states: “[p]ersonal behaviour becomes a concern of the discipline only if it is of such a nature that it undermines public trust in the discipline as a whole or if it raises questions about the psychologist’s ability to carry out appropriately his/her responsibilities as a psychologist.” This raises the question: which magazine covers are considered off-limits for public commentary?

Schabas’s decision disregarded the Supreme Court’s stance in Grant v. Torstar (2009), which held: “freedom of expression and respect for vigorous debate on matters of public interest have long been seen as fundamental to Canadian democracy … all Canadian laws must conform to it.” Why was this principle ignored?

The inconsistency is stark when compared to Europe’s Charter of Fundamental Rights, which states, “Everyone has the right to freedom of expression. This right shall include freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart information and ideas without interference by public authority and regardless of frontiers.” How can a fundamental right in other democracies be so compromised in Canada?

Finally, why did Chief Justice Wagner’s court decline to hear Peterson’s appeal, allowing Justice Schabas’s decision to stand? No prize for guessing the answer.

Dr. Peterson’s case underscores the need for reform in Canada’s regulatory and judicial systems, as long championed by The Globe and Mail and The Toronto Star. The 2007 reforms in England and Wales abolished self-regulation for lawyers, shifting oversight to independent bodies. It’s high time Canada followed suit.

Colin Alexander is an author and former publisher of the Yellowknife News of the North. He holds degrees in Politics, Philosophy, and Economics from Oxford University. His latest book, Justice on Trial: Jordan Peterson’s case and others show we need to fix the broken system, critiques the Canadian justice system, arguing that it lacks public respect and confidence due to fundamental issues and instances of corruption. This commentary was submitted by the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

Explore more on Law, Human rights, Property rights, Rights and Responsibilities, Civil rights

Troy Media

Troy Media is committed to empowering Canadian community news outlets by providing independent, insightful analysis and commentary. Our mission is to support local media in building an informed and engaged public by delivering reliable content that strengthens community connections, enriches national conversations, and helps Canadians learn from and understand each other better.